The Wire Identification Problem

A bunch of n wires have been labeled at one end with alphabetic codes A, B… The wire identification problem asks for an efficient procedure to mark the other end of the bunch with the corresponding labels. The wires run underground so you can’t track them individually and any wire is visibly indistinguishable from any other (except for the labeling).

As you might have guessed, the only way to gain information in this setup is to connect some set of wires at one end, walk up to the other end, and test for conductivity — this would give some partial labeling information. The process may have to be repeated many times before a complete labeling can be constructed. And since each such step involves walking across the distance of the wires, we wish to solve the problem with the least number of trips.

Small Cases

It should be easy to convince oneself that this problem cannot be solved when n = 2 — there’s really nothing we can use to break the symmetry of the situation.

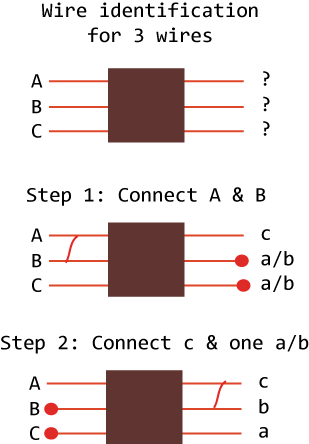

For n = 3, we can use the following simple procedure:

- Step 1: Connect the \(A\) and \(B\) wires at the labeled end, walk up to the unlabeled end, and test for conductivity. The pair that conducts electricity would be \(a\) and \(b\), although we cannot determine exactly which is \(a\) or \(b\) at this point, and the remaining wire is uniquely identified as \(c\). For notation, we use lowercase letters for the labelings that we discover, versus uppercase letters for the given labeling.

- Step 2: Connect the newly identified wire \(c\) with any one of the wires \(a/b\) (recall, we don’t know which is \(a\) or \(b\) individually, only that one is \(a\) and the other \(b\)). Now walk back to the labeled side and test for conductivity of \(C\) with the remaining wires. If we find that \(C\)—\(B\) is conducting, then the \(a/b\) wire we hooked up on the other side was really \(b\), otherwise it was \(a\).

The case n = 4 can be solved similarly with just two trip: Hook up \(A\)—\(B\) on one side and then run conductivity tests on the other side to partition the wires into two groups \(a\)—\(b\) and \(c\)—\(d\); then hook up one from each of the two groups together etc.

So the question is: Can the problem be solved for all n with just two trips?

The General Case

The wire identification problem is one of those puzzles that is deceptively simple in its description, whose small cases are easy enough to solve in the head, and yet a fair amount of math goes into proving the general result.

I first read about this fascinating problem in the Don Knuth’s Selected Papers on Discrete Mathematics — in a short 5-page paper titled The Knowlton—Graham partition problem (arXiv).

Knuth states the following idea, attributed to Kenneth Knowlton, to solve the general problem:

Partition \(\{1,\ldots,n\}\) into disjoint sets in two ways \(A_1,\ldots,A_p\) and \(B_1,\ldots,B_q\), subject to the condition that at most one element appears in \(A\)-set of cardinality \(j\) and a \(B\)-set of cardinality \(k\), for each \(j\) and \(k\). We can then use the coordinates \((j,k)\) to identify each element.

By a theorem of Ronald Graham, a solution involving just two trip always exists for \(n\) wires unless \(n\) is 2, 5, or 9 (On partitions of a finite set).

Knuth in his paper translates the problem of Knowlton-Graham partitions in terms of 0/1-matrices. Lemma 1 in that paper states:

Knowlton-Graham partitions exist for \(n\) iff there’s a 0/1-matrix having row sums \((r_1,\ldots,r_m)\) and column sums \((c_1,\ldots,c_m)\) such that \(r_j\) and \(c_j\) are multiples of \(j\) and \(\sum r_j = \sum c_j = n\)

Let’s use this lemma to label a set of 6 wires (\(A\ldots F\)). Since we can write 6 = 1 + 2 + 3, a rather obvious matrix satisfying the conditions of the lemma is:

\[\left(\begin{array}{ccc}0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & 1\end{array}\right)\quad\]corresponding to the assignment:

\[\left(\begin{array}{ccc}0 & 0 & A\\ 0 & B & C\\ D & E & F\end{array}\right)\]Guided by this matrix, here’s our two-trip identification procedure:

- On the labeled side, hook up wires in the following groups: \(\{A\}\), \(\{B,C\}\), and \(\{D,E,F\}\).

- Walk over to the unlabeled side, run the conductivity tests, and make the corresponding groups \(\{a\}\), \(\{b,c\}\), and \(\{d,e,f\}\).

- Still on the unlabeled side, hook up the wires in the groups \(\{d/e/f\}\), \(\{b/c, d/e/f\}\), and \(\{a, b/c, d/e/f\}\). Note that we still don’t know exactly which wire is, say, \(b\); but we do know the two wires of which one if \(b\) and the other \(c\).

- Walk over to the labeled side, unhook the connection we had made in the first step, and check for conductivity. The sole wire here, say, \(F\) would correspond to the the sole wire from the \(d/e/f\) group on the other side. Similarly, the connected-pair of \(B/C\) — \(D/E/F\) corresponds to the pair \(\{b/c, d/e/f\}\) on the other side. etc.

Extensions

Navin Goyal, Sachin Lodha, and S. Muthukrishnan consider some variants & generalizations of the wire identification problem in their paper The Graham-Knowlton Problem Revisited . In particular, they consider the restrictions to just hooking up pairs in the identification process (in our examples above, we were free to hook, say, 3 wires).